A region divided

The Vero Theatre opened October 1924 on 14th Avenue in Vero Beach and was the center of controversy when the sheriff raided the theater four times from February to March 1925 for breaking Sunday “blue laws.” INDIAN RIVER COUNTY MAIN LIBRARY ARCHIVES, INDIAN RIVER COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The revolt of citizens in Vero Beach helped create Indian River and Martin counties in a break from St. Lucie

BY PAMELA J. COOPER

After much debate and quite a bit of rancor among citizens and politicians alike, Indian River County was born in 1925 through state legislation that carved both Indian River to the north and Martin to the south out of St. Lucie County, leaving three separate counties in the place of one. Local legend has it that the forced Sunday closing of the four-month-old Vero Theatre (later the Florida Theatre and now Theatre Plaza) on 14th Avenue in 1925 was the reason many Vero Beach citizens and officials demanded the creation of a new county. However, complex issues involving state law, moral codes and alleged corruption played major roles in the separation.

LAW AND DISORDER

Sheriff James R. Merritt of St. Lucie County was a key figure in raids made at the Vero Theatre because it illegally remained open on Sundays. The sheriff from 1922 to 1929, he was known for his tough law-and-order pursuit of people in violation of the law. Arrests for possession or sale of alcohol were common. A 1923 government bulletin praised St. Lucie County for taking “quick action against law violators,” according to the Vero Press. A month after the bulletin was published, the sheriff killed an ex-prizefighter known as “The Big Swede” for allegedly drawing his gun. In a dying statement, the fighter declared he had no gun, but Merritt was cleared of his death.

A year later, the sheriff and his men set up an ambush at the Sebastian bridge to catch the John Ashley Gang, well-known for its many run-ins with the law, including the illegal sale of liquor. All four members were shot dead at the scene and carried to Fort Pierce to be put on display.

Local people in Sebastian and Roseland had their suspicions regarding the causes of the deaths. Years later, researchers agreed that it was likely Merritt and his deputies murdered the gang while they were in handcuffs. Court records reveal Theodore Roosevelt Miller and Shadrack O’Dell Davis of Sebastian testified during the sheriff’s hearing that they were at the bridge when the Ashley Gang pulled up behind them.

They were told by authorities to go home, and before they left, they saw the gang in handcuffs. Later Miller and Davis saw the news reports that every member of the gang had been shot dead, with the shots audible throughout the town of Roseland.

The sheriff and his deputies denied they ever put handcuffs on the gang members, and a jury exonerated them.

Miller and Davis repeated their story to people in Sebastian, and Robert G. McCain, who already had a run-in with the sheriff the previous year, began to speak out against the sheriff.

On April 16, 1925, McCain was kidnapped and dragged 20 miles into the woods of Vero and beaten severely. McCain said the men told him he was being punished for signing a petition seeking an investigation into the questionable shooting of the Ashley Gang by Merritt and his men. McCain recognized one of the men who beat him as the deputy sheriff.

When Gov. John Martin was personally shown the wounds of McCain in the governor’s office on April 22, a movement toward county division began to advance quickly. “Quivering with pain as he disrobed in the governor’s office, the man displayed bruises, cuts, and abrasions almost from head to foot, with large portions of his body blue from having been beaten,” the Tampa Morning Tribune reported. A committee from St. Lucie County asked the governor for an investigation of law enforcement conditions. Investigators declared that “a ring” was in control and that “… made it impossible for the administration of justice.” These allegations of lawlessness would play a part in views on county division by state legislators just a month later.

SUNDAY BLUE LAWS

Blue laws were usually designed to enforce moral standards, often restricting certain activities on Sundays. Such restrictions were included in an article under a 1905 act by state legislators that forbade “… any game or sport, such as baseball, football or bowling, as played in bowling alleys, or horse racing …” on Sundays.

Cities and counties often had ordinances that contained similar restrictions, sometimes ignored by citizens and law officers. Many of these laws were repealed over the years. Some are still on the books. In the 1920s, they were often used by authorities taking a strong “law-and-order” stance.

Gus Ruffner was appointed sheriff of St. Lucie County in 1921 after the death of the previous sheriff. The following year, Ruffner lost the primary election to Merritt, who was set to take office in January 1923. However, within weeks of his loss, Ruffner decided to become a strict enforcer of the law in his last few months in office after a year of very little activity by him.

Ruffner’s first law enforcement was to forbid all boxing, a popular sport. A few weeks later, he took more giant steps by declaring everything was to be closed, including restaurants, on Sunday except churches and a few other businesses. “The sheriff stated that it is his plan to enforce the laws throughout the county and to begin with the Sunday laws and then take up each of the other laws and enforce them,” the Vero Press later reported. “It is not likely that Vero will get another taste of Sunday law enforcement in view of the manner in which violations were handled by the authorities in Fort Pierce.”

Controversy ensued when Fort Pierce “calmly ignored” the Sunday law. Less than three weeks later, Ruffner resigned and the governor appointed Merritt sheriff six months before his term in office was to begin. Ruffner was sheriff for just 15 months, but during that short time, he put into place laws and law enforcement that set the stage for Merritt’s tenure as sheriff.

VERO THEATRE CLOSING

The Vero Press published seven pages announcing the opening of the new Vero Theatre in October 1924. The Fort Pierce newspaper had no such companion announcement, perhaps trying to downplay the new theater to the north as unwelcome competition for the Fort Pierce Sunrise Theatre, which opened the year before in 1923.

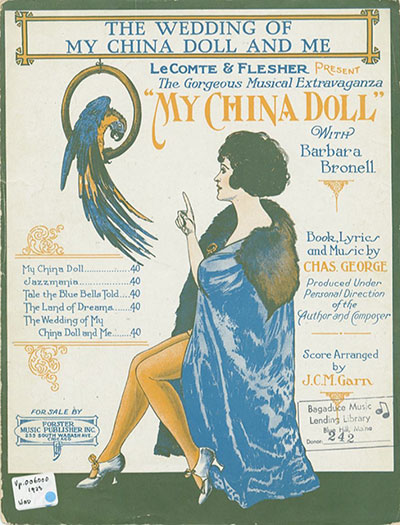

On Sunday, February 15, 1925, the new Vero Theatre was almost filled to capacity for the showing of My China Doll. Merritt and his deputy appeared unannounced, turned off the lights, and ordered everyone to leave. The sheriff then arrested theater manager and owner William Atkin, theater operator Henry Metz and ticket seller William Frick, taking them to Fort Pierce to appear before Judge Angus Sumner, who was summoned to the courthouse. No formal charges were placed against Metz and Frick. The people of Vero expressed indignation at the harsh and arrogant way the arrests at the new Vero Theatre were handled by the officers. Disregard for Sunday laws had been common. Restaurants, for instance, were open all day and night on Sunday in both Vero Beach and Fort Pierce. The Vero Theatre frequently had ads in the newspaper announcing new shows without mentioning Sunday performances, but the public somehow knew they were on.

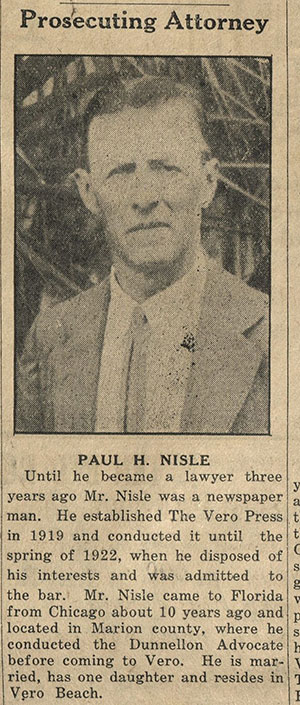

Attorneys Paul H. Nisle and James T. Vocelle, who represented the Vero Theatre Corporation, obtained an injunction from a circuit judge which restrained the sheriff from interfering with the operation of the theater until the cases were heard.

A letter to the editor in the newspaper from the Rev. Albert Brown Cannady of the First Baptist Church of Vero stated the “… operation of Sunday movies in Florida is a violation of the law.” In another letter to the editor, Nellie M. Babb, the park commissioner, pointed out the hypocrisy of Cannady in that the reverend made someone work in his yard on Sunday. In his letter to the editor, J. M. Hatfield of Alabama said, “… I do not believe that people can be forced into the churches by closing everything else to them.”

And so the disputes continued, as did the raids. In the third Vero Theatre raid by the sheriff on March 2, 1925, State Rep. Anthony W. Young was arrested, and the headlines read, “Legislator arrested in Sheriff’s War on Vero’s Sunday Movie.” Young was collecting tickets for the show, and he was also president of the Vero Theatre Corporation. After this raid, the Palm Beach Post printed: “There is a rumor on the streets of a proposed division of St. Lucie County, in such wise, as to make two new counties — one with Stuart as the county seat and one with Sebastian as the county seat.” This discussion had been taking place for several months.

The sheriff raided the theater four weeks in a row. On the last raid on March 15, the sheriff, Young, and attorney Vocelle stood on the theater stage and faced the audience to explain their positions on the matter. The people of the north county were outraged.

In a 1967 radio interview on WTTB, Vocelle spoke about his participation in the division of the county and its roots in the bitterness that he witnessed over the blue laws and the Vero Theatre raids. He stated: “Well, that was one of the most interesting political battles that I have ever engaged in. It began — there had been some agitation.

In fact, when I moved here in 1924, there was some talk about it because Vero Beach and Fort Pierce, there had been sort of a rivalry between them. In fact, sometimes it got to be a little acrimonious.”

DIVISIONISTS

When St. Lucie was formed in 1905 from Brevard County, Fort Pierce was designated as the county seat. In less than 20 years, the people in the northern part and the southern part of the county wanted to separate and form two new counties to allow the people to govern themselves for economic reasons.

They were called “divisionists,” which is a word used often in previous decades around the United States due to county divisions in many states. From Stuart to Sebastian during the month of April 1925, mass meetings and gatherings frequently occurred consisting of those who supported the division and those who opposed it. The anti-divisionists wanted a referendum placed in any bill to give the citizens of St. Lucie County an opportunity to vote on the question of division.

More than 130 divisionists from Vero, Quay (Winter Beach), Wabasso and Sebastian boarded a train in early May from the Vero station to Tallahassee in support of a bill for county division. Objectors also attended but were outnumbered three to one.

That same month the House approved the new county with changes in boundaries, and Vero was named the county seat. Many House members were no doubt still affected by the wounds McCain had shown to the governor a month earlier. In the Senate, the hot debate over the creation of Indian River County lasted three weeks.

More than 200 citizens gathered at the bandstand on Fourth Street in Stuart to discuss and approve the county division. THE STUART MESSENGER

The headlines portray what the people of Fort Pierce were feeling at the time. They considered this fight to be “highly detrimental to the county.” Petitions were being circulated throughout the county for the anti-divisionists. FORT PIERCE NEWS-TRIBUNE

The vote was delayed because “A letter was introduced purporting to be signed by A.W. Young, in which the writer stated that his ‘policy as opposed to county division in any form is well known to the people of St. Lucie County,’” the Miami Herald noted. In the 1922 election, Young had been elected the Democratic representative of St. Lucie County. In his campaign, he declared he would “oppose county division,” the Vero Press reported. However, Young apparently changed his view following the arrests at the theater and the uproar that followed.

The bill creating Indian River County finally passed in the Senate, 23 to 9, on May 28, 1925. The voters’ referendum was killed by a close vote, taking the choice out of the hands of voters. After the official split between the counties, the newly formed county of Indian River had a population of 5,400 and St. Lucie had a population of 6,250.

For some time, the people of Stuart had wanted the southern half of St. Lucie County and the northern part of Palm Beach County. The Martin County bill was passed by the House on May 27, 1925, and the Senate passed it on May 28. This new county was named after Martin while he was in office. The governor signed the bills on May 30, creating both Martin and Indian River counties, effective June 29.

CELEBRATION

Immediate plans were made for a huge celebration in Vero Beach on Monday, June 29, to include people from both of the newly formed counties. No less than 4,000 people attended. Barbecue, baseball games, contests, parades, fireworks and speeches happened throughout the day until midnight when the Vero crowd could finally say they were officially in a new and separate county.

At the celebration, William Jennings Bryan, a three-time candidate for president and noted Scopes trial lawyer, may have given his last speech in honor of the Indian River County celebration as he died less than a month later. A historical marker can be viewed in front of the Heritage Center on 14th Avenue commemorating this event.

Young, who was introduced as the “father of Indian River County,” also spoke at this historic event.

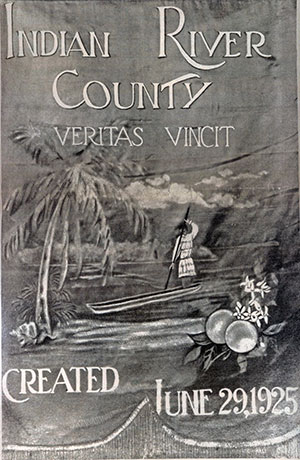

During the celebration, Irene Young, the representative’s wife, presented a banner for the creation of Indian River County bearing the words: “Indian River County, Veritas, Vincit (truth prevails or conquers or the truth shall prevail), created Jun 29, 1925.” Only a picture of the banner could be found over the years, and not the banner itself. The picture was donated by James Tippin to the local library.

The new county offices were first located in the Seminole Building on the corner of 14th Avenue and 21st Street. All convicts in the custody of St. Lucie County were turned over to the authorities of Indian River County on June 30. The Fort Pierce newspaper reported nothing of the event except for a small paragraph on William Jennings Bryan.

Indian River County owes its creation to law enforcement actions of the sheriff, especially of Sunday blue laws against a new and popular Vero Theatre, and the divisionist sentiments that were sweeping the state and the country during the mid 1920s.

Pamela J. Cooper is a retired librarian, historian, genealogist and lecturer in Vero Beach.

See the original article in the print publication

The four-story building mentioned in the top headline was never built. However, there is a picture showing the ribbon cutters, which somehow removed some of the people from the original photograph. VERO BEACH PRESS

Mrs. Anthony W. (Irene) Young sewed this banner and gave it to the county officials for the county celebration on June 29. The banner has not survived, but this picture was made available by Jim Tippin, son of George T. Tippin, who was a part of the delegation that went to Tallahassee.

Do you have legacy business? Let us know about it.

Call 772.940.9005 or use our contact form

FIRST OFFICIALS OF INDIAN RIVER COUNTY

Prosecuting Attorney – Paul H. Nisle, Vero Beach

Clerk Circuit Court – Miles Warren, Fort Pierce

Tax Assessor – George T. Tippin, Vero Beach

Supervisor Registration – Albert Schuman, Sebastian

Sheriff – Joel W. Knight, Vero Beach

Tax Collector – Gordon Olmstead, Wabasso

Superintendent of Public Instruction – W. E. Riggs, Vero Beach

County Commissioners – John M. Atkin, Vero Beach; O. O. Helseth, Oslo; Donald Forbes, Quay; George A. Braddock, Sebastian; J. W. LaBruce, Fellsmere

Board of Public Instruction – Louis Harris, Vero Beach; William E. Feazel, Fellsmere; Dr. David Rose, Sebastian

FIRST INDIAN RIVER ACTS APPROVED

1. Regulating fishing in Indian River.

2. Authorizing Indian River County to construct roads and bridges in special road and bridge districts either by letting or without letting by contract.

3. Regulating placing of advertising signs in St Lucie County.

4. To prohibit placing of advertising signs upon the property of another without written consent of the owner, and to prohibit placing of advertising signs on the rights of way of public highways in Indian River County.

5. Authorizing Indian River County to issue time warrants for raising funds to equip county offices, and for other purposes in connection with establishment of the newly created county.

6. Creating special taxing district in Indian River County to be known as Vero Beach Inlet District.