Life on Florida’s last frontier

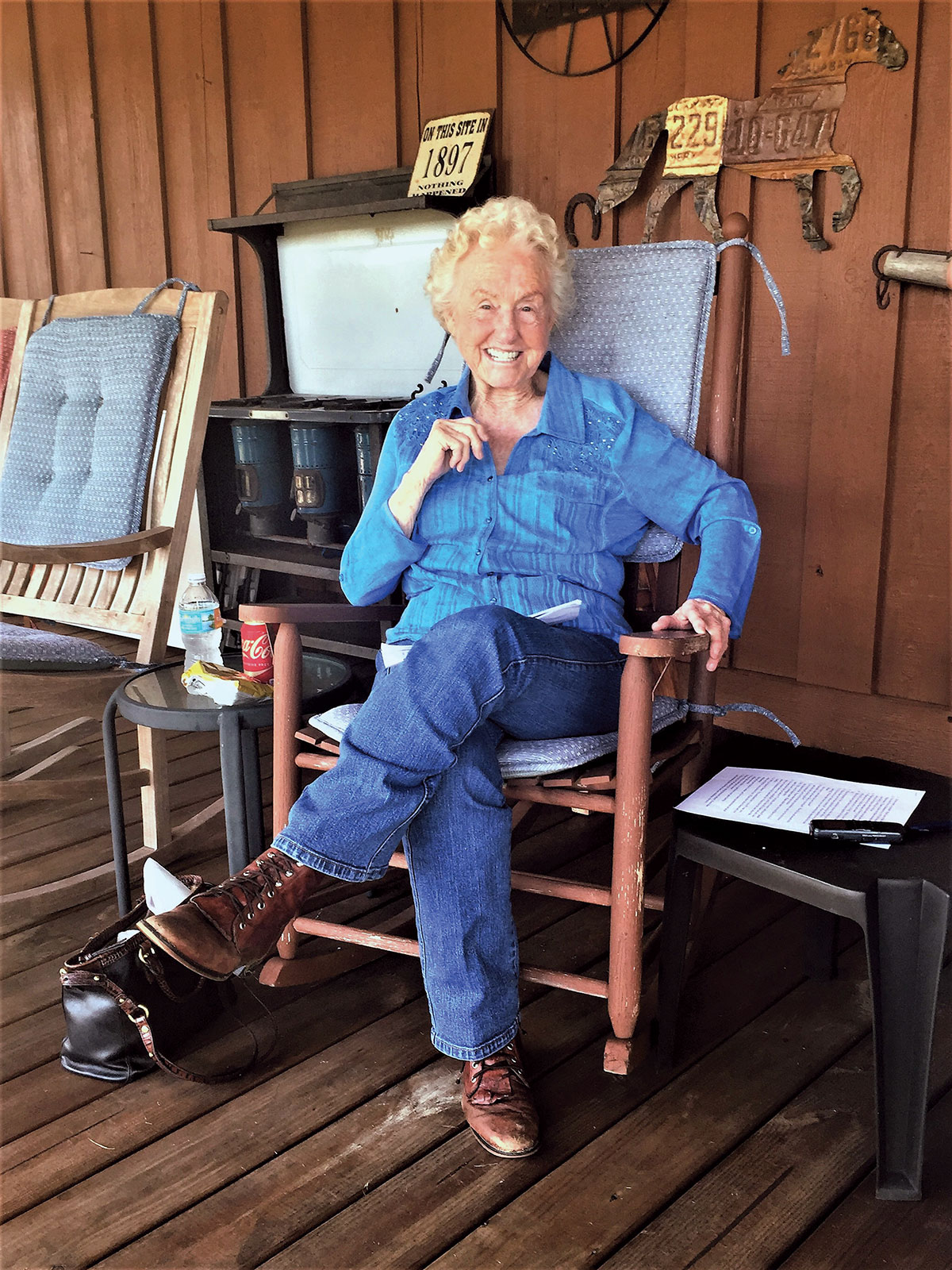

Wall shares her homespun stories about the Cracker lifestyle while rocking on the porch at her High Horse Ranch. RICK CRARY PHOTO

Cracker grandam shares her love of the Old Florida lifestyle

BY DONNA CRARY

Florida’s Cracker culture is alive and well thanks to Indiantown’s homegrown celebrity Iris Wall. The 87-year-old cowwoman proudly promotes and enjoys speaking around the state about the Cracker lifestyle.

She understands firsthand about adventure because she lived in South Florida when it was one of the last frontiers. Awarded Woman of the Year by the Florida Department of Agriculture and inducted into the Florida Cracker Hall of Fame, the fifth-generation Floridian talks in an animated, down-home manner about the people in her native state.

“Being a Cracker is more a culture than anything else,” Wall says. “Most of the Crackers that I know are a long shot from royalty and many of them have made money. They are a very generous, kind people and have a great respect for women. They are proud and well educated, not in book learning, but in pure basic life.”

The vivacious and witty rancher speaks about old Florida — a place that most can only imagine in a book or a movie. She shares her Cracker tales of growing up on the back of a horse while hunting for cows out in the swamp or scrub. The pioneer knew the perfect way to kill a gator for its hide and to survive, she and her family simply lived off the land. She married her childhood sweetheart Homer Wall, and together they went from cutting fence posts to building a prosperous lumber business. Today, preserving the agricultural traditions of Old Florida is Wall’s passion. A children’s book has been written about her and she enjoys speaking to groups and imparting her folksy words of wisdom.

DEPRESSION DAYS IN DIXIE

The expression of seeing a glass half full perfectly describes Wall’s optimistic view on life. She was born Iris Pollock in Indiantown in 1929 — the beginning of the Great Depression. To many, those difficult and depressing economic times would harden one’s outlook, yet Wall shares a different perspective.

“To be born in 1929 was in itself bad luck. The good side of the story was I didn’t even know there was a depression,” she recalls. “Everybody I knew was the same — poor. Nobody had any money, but we had everything else in the world we needed. We had such a good time living that we rarely thought about what we didn’t have.”

South Florida back then was mostly one big swamp and hammock. As a girl, Wall was a red-haired, freckle-faced tomboy — with a fiery disposition to match. She loved nothing more than to freely explore the outdoors. While most girls were learning to sew, crochet and quilt, she preferred life in the saddle.

“I cried every time I had to learn to quilt,” she says. “Grandma would finally get enough of it and say, ‘Go on outside!’ I was a cowboy — still am an old cowboy.”

The Florida landscape was her playground. Wall’s sister, June, John and James Holt, who later became the sheriff for Martin County, were her constant companions, and they had good old-fashioned fun. They swam and fished for trout in sand-bottomed ponds, hunted, camped out in the woods and rode their horses until the sun set.

“That’s the way we played,” Wall remembers. “People ask, ‘What hobbies did you have?’ I didn’t even know what a hobby was!”

CRACKER COW HUNTING

Wall and her family were cow hunters, which meant they were Florida cowboys who track cows through dense woods or swamp and return them to the herd. Those were the days of open range before the state required cows to be fenced in. They would hunt, pen, brand, doctor and drive cattle all day long.

“I just pure loved to cow hunt,” Wall says. “I wouldn’t sleep a wink the night before, for fear of being late.”

She remembers leaving for cow hunts with old friends like Bobby Hamrick at the crack of dawn with a pack of dogs and gathering about a hundred head of cattle. The popping sound of the cow whip guided the cows in the right direction.

“We’d amble along with them cows, and if we heard the whips popping behind us, we went too fast, and we hold the cattle up,” the cowwoman says. “But if we heard the whip popping ahead of us, we’d have to speed up. We’d hear those whips popping and we’d know where those cattle were.”

Wall fondly remembers cow hunting trips with her father when they would stop, build a campfire and have dinner Cracker-style. Her dad would cut and trim some palmetto fans and use them as skewers, stick the fatback on one end, and plant the other end in the ground by the fire.

“When that bacon cooked, it would be so good,” she said. “And we’d have a sweet potato, a cold biscuit and that was dinner.”

LIVING OFF THE LAND

The Depression years followed by World War II were tough economic times for families like Wall’s. Just surviving was a real job. Yet, the fish and wildlife were plentiful, which made it easier for them to eat and live off the land.

“You could say, ‘I’m going to kill a mess of quail for dinner,’ and you’d just go out there and come in with a vest packed with quail,” Wall recalls. “We didn’t hunt for sport. If we wanted meat, we’d kill a deer, quail, or whatever we needed and that’s all we killed.”

All the Crackers Wall knew back then mostly ate wild hog, venison, chicken, wild turkey, quail and fish. Her family raised cattle, yet they never considered eating beef. “Beef was a cash crop,” she says with a chuckle. “We weren’t going to kill a cow that we could sell.”

MAKING DO

The hardy Crackers of South Florida managed to live without electricity, phone service and other modern-day inventions. In Indiantown, most babies were delivered at home with Aunt Sis Savage as a midwife. Practically everyone went around barefoot, since they didn’t own a pair of shoes. Wall picked up her first telephone when she was in the sixth grade. It might as well have been a foreign object from a distant planet, because she didn’t know which end of the phone to talk into.

Those were the days when doctors made house calls. Dr. Julian Parker, who everybody loved, drove out from Stuart in his Model A Ford. He treated his patients whether they had the money or not.

Washing clothes for Wall’s family was a weekly and social affair. The women came together and washed in boiling tubs over a fire, while chatting and watching the children play.

Catching the morning train that came through Indiantown was a daring adventure. Wall recalls the bold and primitive way a passenger got on board. “We’d take a newspaper, wad it up, and stand out in the middle of the tracks and wave it back and forth,” she says. “We had to wait until we heard the train coming. And the train would stop — screech!”

MARRIAGE TO HOMER

Iris treasured the marriage and life that she built with her husband, Homer. Their 47-year love affair began for her while they were attending Warfield School in Indiantown.

“When we were in the sixth grade, we put on a play called Aunt Drucella’s Garden,” she recalls. “I was Aunt Drucella and Homer was the gardener. I’ve loved the gardener all my life.”

They became high school sweethearts while attending Stuart High School. In their senior year, Homer was offered a football scholarship to the University of Florida, but turned it down, so he could marry Iris on Sept. 12, 1948.

GIGGING FOR GATORS

The young couple started out with nothing but an eagerness to work, so they made their living cutting fence posts and fencing other ranches, while living in the wilds of the Everglades. They made $150 a month, barely enough to eat, so they gator hunted to survive those tough times.

“Good Lord, for a little gator, 4 to 5 feet long, you could get $35 to $45 — Crackers are gonna gator hunt!” she says. “That’s just the way it was and that’s what we did. We gator hunted!”

Wall recalls the precise way they subdued these mammoth, iconic creatures.

“We used a .22 and you’ve got to know exactly where to shoot them — right in the eye—or you can’t kill them,” she says.

The prized part of the gator was its hide or belly that they sold. They carefully skinned it to avoid cutting a hole, or it would reduce the price of the hide. Large older gators that had big hides or button hides were considered less valuable.

“We killed many gators — not to eat — but for the pure money — for the hide. It bought many a pair of shoes and probably built the Baptist church here in Indiantown,” she says with a wink and a smile.

BUILDING FAMILY AND BUSINESS

Eventually in 1962, the Walls partnered with Jack and Faye Williamson to start their own business, WW Lumber, in Indiantown. After three years, the Williamsons sold their half of the business to the couple, and today the lumber company is thriving with six locations in central and South Florida.

In 1975, the couple also purchased and restored the Seminole Inn in Indiantown. Built in 1926 by S. Davies Warfield, the historical mission-style hotel had been neglected and fallen on hard times.

So with a lot of work and special care, the couple refurbished the inn as their gift to Indiantown. The upstairs is decorated with hand painted murals depicting historical scenes of the Seminoles, the lobby offers an inviting sitting area with a fireplace to read or chat, and the overall ambience evokes an Old-World charm. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, today it is a landmark that provides Southern dining and cozy accommodations for guests.

The Walls were blessed with three daughters — Terry, Jonnie, and Eva — seven grandchildren, and nine great-grandchildren. As the matriarch of the family, Wall’s children and grandchildren often turn to her for guidance, direction and support.

“My mother is the Gorilla Glue of our family,” Jonnie Flewelling says. “She is the one that has kept us balanced and together, somewhat in line and tries to keep what is real and important always in front of us.”

Homer passed away on Sept. 26, 1994. “I really didn’t think I could live without him, but God has given me the grace to keep going,” Wall wrote in her booklet Cracker Tales. “Homer and I bonded in a marriage that could not be broken. Troubles, trials, heartache, even death has not broken that bond.”

COMEBACK COWWOMAN

When Homer died, little did Wall know at the time that she would begin a new chapter in her life. The following year, her daughter Eva encouraged her to participate in Florida’s 1995 Cattle Drive. They along with her grandchildren and several hundred cattlemen rode their horses and drove 1,000 head of Cracker cattle from Yeehaw Junction to Kissimmee, to celebrate Florida’s 150-year anniversary.

They rode for a week along the dusty trail, camped, told stories around the campfire and slept on the ground under a starry sky — just like their Florida ancestors. Perhaps, it was listening to the storytelling around the campfire or maybe it reminded her of her own cow hunting days long ago, but something ignited a spark with this cowwoman and rekindled her passion for Old Florida.

At the event, Wall renewed old friendships, people she had not seen since she was a teenager. They kept in touch following the cattle drive and cattle organizations throughout the state began to seek her out. She rode the cross-state Florida Cracker Trail the following year then became active and later served on the boards of the Cracker Horse Association, the Cracker Cattle Association and the Martin County Farm Bureau for many years.

“After my dad died, I saw the blossoming of this person and this personality that was as big as my father’s personality,” Flewelling says. “How many women are strong enough after the loss of the love of their life to go back and pick up a thread that has been laying for 49 years — pick up and re-enjoy all the things she did when she was a young girl and a woman?”

CRACKER EDUCATION

Education is important to Wall, and she enjoys opening children’s eyes to the natural beauty of Florida and its agricultural traditions. For more than 10 years, she has been a regular at Warfield School telling her Cracker tales. She also has hosted field trips to the Seminole Inn and the High Horse Ranch, giving students hands-on teaching about cow hunting and ranching, washing clothes without electricity and riding in wagons.

Her story inspired Carol Rey, a former teacher at Warfield, to write a children’s book, Iris Wall — Cracker Cowgirl. The book captures Wall’s life, love for cow hunting and teaches about Cracker living.

“People are still so fascinated with the cowboy and the cattle life because at heart they embody the American pioneer spirit of adventure,” Rey says.

Wall has also spoken to many groups throughout the state that include the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, The Villages near Ocala, the Stephen Foster Folk Culture Center and the Stuart Heritage and the Elliott museums. Her message is simple and clear — protect agriculture and preserve the land.

“I want people to realize that grass doesn’t grow in concrete, and we better save some of our state or it will be gone,” she says. “Ranching, farming and dairy industries support families and do a lot of good. When we get to the place in the United States that we can’t feed ourselves, we’re going to be in a very serious condition.”

HOME ON THE RANGE

Today at 87, Wall remains active and engaged with her community in Indiantown. She’s an avid reader, teaches a Bible study to local women, hosts and cooks Sunday family dinners and still makes time to take care of her big love — the High Horse Ranch. There she raises cattle and even keeps some Cracker cattle as living links to Florida’s history. She still enjoys riding through the pastures among the palmetto and oak hammocks, where deer freely roam. Wall is passionate about respecting the land, and true to the Cracker spirit, stays connected to and draws an inner peace from it.

“I love the land — I love cattle — and I love pasture,” Wall says. “They’re not making any more land and I want to take care of and do what’s best for it. It is a very simple life, but it’s rewarding, too. I don’t worry about nothing when I’m out here. I look at them little old cows and watch them plunk along. If that won’t calm your nerves, nothing in the world will.”