Researcher for the ages

On the 305th anniversary of the sinking of a fleet of treasure ships off our coast, friends and family members pay tribute to the researcher who helped reconstruct these shipwrecks and many others during the Spanish colonial period

BY ALLEN BALOGH

In 1970, a University of Florida Ph.D. student found the location of The Nuestra Señora de Atocha and the sister ship Santa Margarita, The Spanish galleons carried over $400 million in gold, silver, and emeralds and had succumbed to a vicious hurricane in the Dry Tortugas. The Ph.D. student became the foremost international authority on Spanish Colonial history. Without Dr. Eugene Lyon’s contributions, there would be an empty spot in our history.

Lyon, an international expert on Spanish Colonial Florida and the Spanish maritime system, died May 3 at the age of 91 in Vero Beach.

I first spoke with Dr. Lyon in the summer of 1987. He was a professor at Indian River State College. A true gentleman, he was gracious and unassuming. I told him where we were in the hunt for the Spanish galleon, Urca de Lima, south of the Stuart Inlet. He assured me the State of Florida was wrong about the location of the Urca being at Pepper Park in Fort Pierce and that I was either very close to or on top of it. His words, “Keep looking.”

Dr. Eugene Lyon was born and raised in Miami. He was the son of Homer and Katharine Lyon. In 1951 he married Dorothy Mathews. He had a brother, Homer, Jr. who was Gene’s twin in every sense. Living in Miami, he and Homer learned to speak Spanish at an early age. The children of Dr. Lyon referred affectionately to their uncle as another father. “We were lucky to have two dads,” said Peggy.

VERO-BOUND

Out of high school, Eugene Lyon received an ROTC scholarship and was soon on his way to to the University of Florida in Gainesville. After graduating, he served in the Navy during the Korean War. Following his military service, he attended the University of Denver to receive his master’s degree. He returned to his birthplace and served as assistant city manager of Coral Gables. He then moved to a small town called Vero Beach, the home of “Historic Dodgertown,’’ the spring training facility of the Los Angeles Dodgers. He served as city manager there from 1958 to 1961.

Eugene Lyon left Vero Beach and took his family to the Republic of Congo to help establish the Congo Polytechnic Institute. His son, Kenny remembers: “Immediately upon moving into our new house on the outskirts of the city between a UN barracks staffed with troops from India and a corn field that was all that separated it from, well, Africa, replete with rebels and nightly drums, mild Gene was forced to negotiate a strange world in a strange language.”

A NEW MISSION

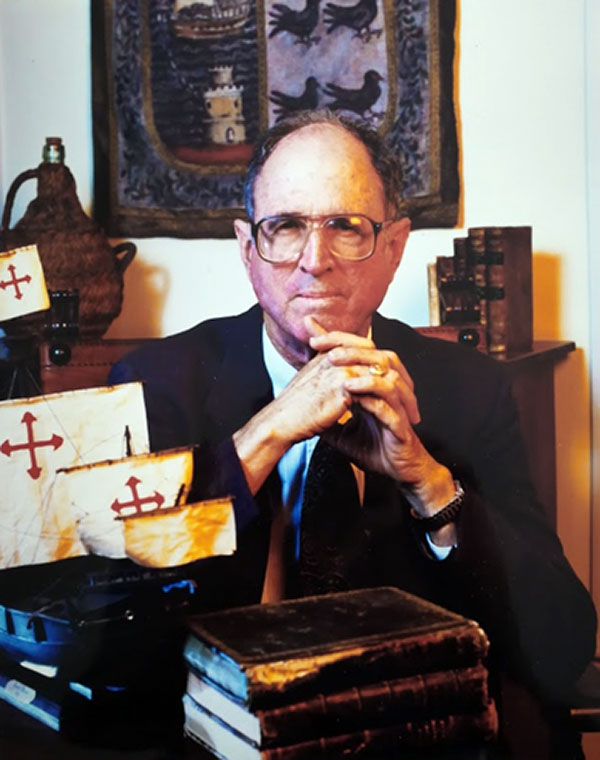

In his thirst for history, Lyon returned to Florida where he received his Ph.D. in Latin American history from the University of Florida. Now he was on a mission, to research, and discover the impact of the Spanish empire on the Americas. He spent untold hours in the archives of Seville, Spain, reading and interpreting worm-eaten primary documents.

Dr. Lyon has published numerous documents and letters, to name a few: The Enterprise of Florida, Pedro Menendez de Aviles, the Spanish Conquest of 1565 – 1568, and The Search for the Atocha. He also wrote several articles for National Geographic.

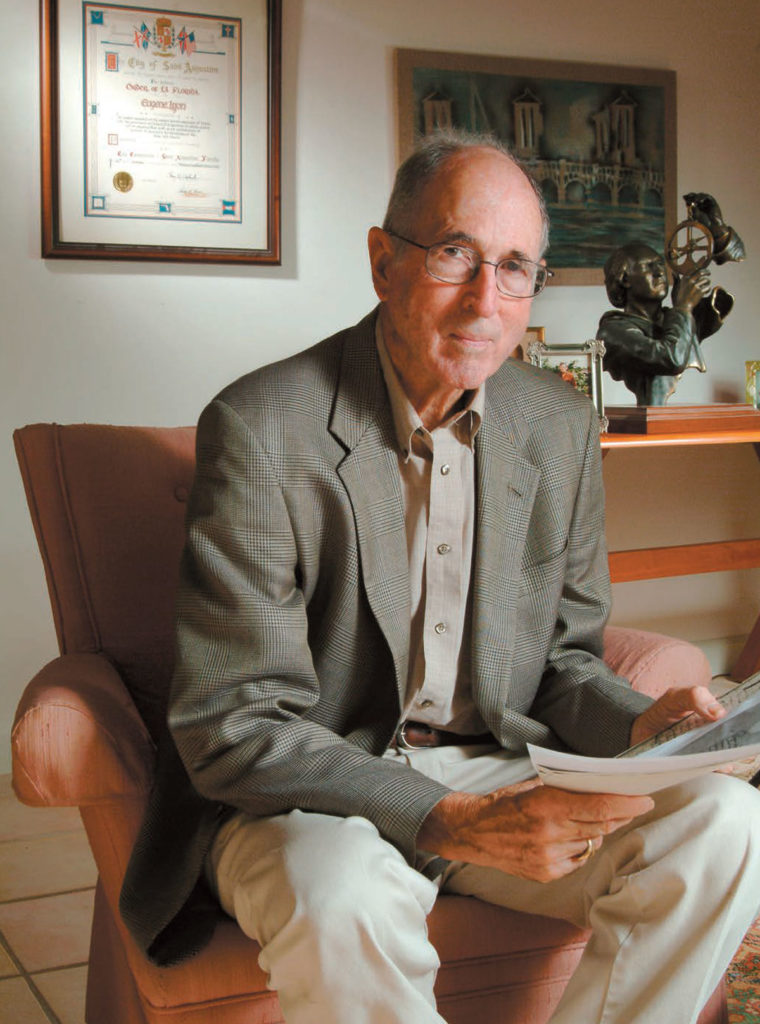

Flagler College welcomed Dr. Lyon, who directed the St. Augustine Foundation for 14 years, collecting over a thousand reels of film related to Spanish Florida. His travels included Spain, Colombia, and Cuba. His work in resolving the Spanish layouts of St. Augustine granted him the city of St. Augustine’s highest honor, the Order of La Florida.

COLUMBUS CONTROVERSY

In 1985, Dr. Lyon found documents showing the course of Columbus’ first voyage to the New World was 65 miles north of the previously accepted route. Dr. Lyon wrote a controversial National Geographic magazine article with the new information. He opined that most of Columbus’s history was based on the imagination of writers. Why? The original logs were given to Isabella and Ferdinand by Columbus. Supposedly, the logs were placed in the Biblioteca in Seville. Spain. Unfortunately, the most famous documents of the time had disappeared.

Dr. Lyon lamented that October 12, Columbus Day, is the Dia de la Raza or the day of the race. It celebrates Spain’s race to conquer the New World in the name of Christianity, not so much as the discovery of the Americas.

NUESTRA SENORA AND SISTER SHIP

Nuestra Señora de Atocha was named after the most revered holy shrine in Madrid, Spain. The galleon was heavily armed with 20 bronze cannon and served as the Almirante of the Spanish Fleet. Built in Havana, the Atocha departed Havana Harbor and within a day sank from a hurricane on Sept. 6, 1622. Over 40 tons of silver from Peru and Mexico, gold and emerald from Columbia, and pearls from Venezuela and Panama littered the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. A second hurricane hit on Oct. 5, creating more devastation. The value? An estimated $400 million plus lay on the ocean floor in the Florida Keys.

But exactly where?

The inimitable Mel Fisher learned of the Nuestra Señora de Atocha and Santa Margarita in John Potter’s book, Treasure Divers Guide. Mel was so confident of the location and his ability to find it that he departed his successful work on the sites of the 1715 Fleet in Sebastian and Vero Beach. Soon, Mel, his family and crew were in the Florida Keys, Matecumbe Key, searching for these two magnificent galleons.

Mel Fisher also heard that his friend, the former city manager of Vero Beach, was on his way to Spain to finish his doctoral degree in Latin American history. Specifically, the archival library, “Archive of the Indies” in Seville, Spain. Mel asked, “Gene, please keep an eye out for any documents with the name, Nuestra Señora de Atocha.

The following year in 1970, Dr. Lyon was in the archival library scouring nearly 400-year-old, worm-eaten Spanish documents. Preternaturally, a hand-written document revealed the names: Nuestra Señora de Atocha and Santa Margarita. The hand-written note also indicated that survivors set up a campsite on an island, “Cayos del Marques.”

Through determination and genius, Dr. Lyon was able to narrow down the location of the galleons. This information led Mel Fisher and his family to move from Matecumbe Key to Key West and spend the next 15 years, searching and finally finding both galleons between the Marquesas Island and the Dry Tortugas.

One of the best first-hand anecdotes is told by John Brandon, famed 1715 Fleet researcher and exploratory diver,

I remember when I was in my late teens, in the early 1970’s, and very involved with Mel Fisher and the search for the Atocha sunk off the Marquesas Keys, west of Key West. My hometown was Fort Pierce when not in Key West, and Gene lived in Vero Beach just to the north of Fort Pierce. Gene would frequently give me rides from Key West back to Fort Pierce or from Fort Pierce to Key West as he made his trips back and forth. (I didn’t have a car at that time.) Even at that young age I had read everything I could get my hands on concerning early Florida history and Gene was only too happy to carry out hours long discussions with me on this subject as we drove.

One of the most interesting and significant stories Gene related to me on one of these long drives was how he was able to determine that Mel should be looking for the Atocha off of the Marquesas Keys and not the Matecumbe Keys located in the middle Florida Keys.

The initial Spanish research said the Atocha had sunk off the last key of Matecumbe. Everyone, including Mel, believed this was either Upper or Lower Matecumbe Key and everyone concentrated their efforts in that area.

It was Gene who finally realized that when the Atocha sank in 1622, that the Chief of the Calusa Indians, the Native American tribe that dominated all of south Florida from Lake Okeechobee through the Keys was named Matecumbe. And therefore the, “Last Key of Matecumbe” was in fact the Marquesas Keys. The last key that Matecumbe held dominion over.

Based on Gene’s interpretation of the historical research and his reference to the Isla de Marques, Mel moved his operation to Key West and the Marquesas Islands to search for the Atocha, and the rest as they say, is history!

Dr. Lyon chronicled his research of the 1622 Fleet in his book, The Search for the Atocha. It may be purchased at Mel Fisher Treasures in Key West, Mel Fisher’s Treasure Museum in Sebastian or on-line at melfisher.com. The Key West location also offers visits to the Atocha and Santa Margarita sites. He served as Chair of the Board of the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society. In 2005, Dr. Eugene Lyon received the Mel Fisher Lifetime Achievement Award.

We’ve traveled to the memorable stories about Dr. Lyon, the personal stories from his children, friends, and colleagues.

PEGGY LYON, MEET MY MOM AND DAD

Here is one of my dad’s favorite stories that I personally have heard him tell many, many times to many, many people. I think he would love having me tell it to you!”

When our dad and mom met at a fraternity dance at the University of Florida in December of 1951 it was about as close to love at first sight as you can get, Mom with her lovely auburn hair and dressed in a floor length purple gown busy forming a life-long love for her soon to be alma mater Florida State University, and Dad such a handsome young life-long University of Florida Gator. It wasn’t long before Dad had given Mom his fraternity pin and one hot day in Apopka, Florida on June 15, 1952, they were married in a small church before family and friends. But in between that fraternity dance, the fraternity pin, and the wedding was the Korean War and Dad’s naval service.

Near the end of Dad’s military term of service, the navy asked him to extend his duty as helmsman by six months. He was an excellent helmsman, with an exceedingly steady hand and eye, and the Navy wanted to keep him a bit longer if they could. Dad advised the Navy officials that he was sorry but any extension was impossible, even a relatively short six-month extension, because he had met this wonderful girl and was planning to get married.

At this point in this much-loved story, Dad always paused and said, in explaining why he was not interested in extending his naval service, “You see, I’ve met this girl.” And because of that fateful decision, our father was not aboard his vessel, the U.S.S. Hobson, on the night of April 16, 1952 when the U.S.S. Hobson was cut into two pieces by the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Wasp, sinking our dad’s former naval ship in less than five minutes with 176 members of her crew lost at sea. Our dad always said that the decision not to extend his tour of duty with the Navy and to marry our mom saved his life.

So here is the companion story of how Dad saved our Mom’s life years later: Life-saving turnabout was fair play. Fast forward to Leopoldville, Congo, in the early 1960s.

After stepping down as city manager for Vero Beach, our dad’s next adventure took the family to Africa. With two young children, my brother Kenny and me, and my mom pregnant with their third child, our sister Katie, our family relocated to Africa where Dad was business manager for an association of churches that formed the Congo Polytechnic Institute.

It was a dangerous time to be living in the Belgian, Congo. The windows and doors of our missionary duplex were covered with metal bars for protection and a night watchman patrolled our yard while a guard armed with poison-tipped arrows was stationed at our dad’s place of work.

Driving on the outskirts of Leopoldville one day, my parents were stopped by armed guards at a check point. Demanding money, which for our missionary family was in short supply, one of the guards put a gun to our mother’s head as she sat in the passenger’s seat of the small Volkswagen that they drove. Our father carefully exited the VW bug, went around to the guard and gently pushed the gun away from our mother’s head, gave the man what little money he had, got back in the car and drove her safely away. And Dad saved Mom’s life!

KENNY LYON, PROUD AND LOVING SON

To his friends, he was plain old Gene Lyon. And everyone was his friend.

If he was at a gas station in Georgia, he had a southern accent. In Sevilla he was Andalusian; in Madrid, Castilian. He was never talking down, or pandering he simply had an innate desire for everyone to feel comfortable. This is character trait number one.

But to us? To Peggy, Katie, Beth and myself? To his children and to our mother, his beloved wife, Dottie he was “D.” Simply D. Or, more formally, “Big D.” When we first arrived in Seville, Spain, Dad hired a flamenco guitar teacher for Peggy and me. We were 15 years old and 13, respectively. The teacher’s fractured English led to a series of malapropisms, to “D” from d-ao-di for Dad and “M” ma-o-mi for Mom. The names “D” and “M” stuck.

We the children, dragged on a life-long adventure spanning oceans and continents, developed a language all our own. But that name was given in Spain; first there was Africa.

In 1961, disillusioned by corrupt small-town politics, Gene traded the life of a city manager for that of an educator of future city managers. Or, more accurately, an enabler of said education. He packed up his two children, five and eight, and soon-to-pregnant-with-a-third wife, and moved to Leopoldville, capital of the former Belgian Congo. Politically speaking, he was leaping from pan to fire: Belgium had exemplified every evil of imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism in their rape of the Congo. Now they were leaving, and leaving behind a nation unable to govern itself. Gene came to help organize a school to teach political science to the generation of Congolese tasked with managing the nuts and bolts of their forced new world.

Immediately upon moving into our house on the outskirts of the city between a UN barracks staffed with troops from India and a corn field that was all that separated it from, well, Africa, replete with rebels and nightly drums mild-mannered Gene was forced to negotiate a strange world in a strange language. Our house came with barred windows (that proved insufficient for their intended task) and a guard (ditto); currency had to be changed on the black market, our refrigerator ran on kerosene and there were no eggs (for starters). This leads to character anecdote number two.

My father slipped into new languages the way a Beverly Hills housewife changes outfits. I used to joke that he could get off a train in a new country, wander for an hour, and come back to the station speaking the language. The complexities of navigating the new life in Congo must have been daunting, to say the least. It wasn’t easy for my mother to deal with a completely foreign set of ingredients (bless her and her southern dietary orthodoxy), it wasn’t easy for Peggy and I to see lepers, grown men with hands cut off (thank you, King Leopold), and bodies by the side of the road and it probably wasn’t even easy for Katie to be born. But starting and running a school, dealing with political intrigue and the black market in order for the school to survive… remarkable.

As with all his other remarkable achievements and abilities, I could never get my father to glory in them or even acknowledge their essential exceptionality. But we saw them.

My memories of that time are many and vivid. I will save dwelling on them for another time; I’ll just throw out a few things: trips into the interior in a Land Rover, rattling down red dirt roads for days on end; a trip to the coast for holiday, eating barracuda and Mom getting sick with ciguatera; Sundays taking our old VW bug onto a ferry (two planks over the rushing water of the Congo River onto a rusting hulk) to cross to Brazzaville for ice cream. Having our full-time guard wake D up to tell him, “Monsieur, I must tell you, your car it has been stolen…” Break-ins and the crowning incident – as the political situation deteriorated: a full-on gun battle between UN troops on one side of our house and rebels (of some kind or description) on the other. Bullets flying right through, lodging in the walls.

(Family lore has it that I kept sleeping until I was shaken awake and dragged under the bed) When we finally escaped (and D admitted to me years later that it was, indeed, an “escape,” a white-knuckle ride to the airport, bribes, suspense...) we went to Switzerland the anti-Africa to see snow for the first time, and then back to Florida for his next life chapter: history. After a few jobs the best of which was teaching Western Civilization 101 at the local community college. D returned to the University of Florida to work on his doctorate while Dorothy (“M”) made ends meet by managing two public libraries (and a bookmobile, as she was proud to point out).

This led to a Fulbright, a dissertation, and Spain. And, eventually, a treasure.

BETH LYON, DAD OUR MENTOR

My story is about my Dad as a mentor. He was the most generous person I have ever known. He shared everything including his passion for history. His love of history was infectious. His work had a particularly direct influence on my mom, his brother, and me. He gave us the privilege and joy of working by his side.

My dad’s twin Homer took enormous pride in his brother’s work. He learned to read the old Spanish script and pitched in with translations and long conversations that enriched my dad’s work. I tagged along with Dad and his teams to Madrid and to Cuba, where I put on my white gloves, helping to identify documents of interest for his research and to prepare old documents for microfilming.

I learned Spanish because of and from my dad, and most importantly I learned from his example that an introvert can succeed as an outsider in uncharted territory. When I decided to follow in my big sister Peggy’s footsteps and become a lawyer, Dad and I joked together that “come the revolution” historians would be seen as unnecessary beings who would be dispatched, and that social justice lawyers like me would follow right behind. He knew that lawyers and law scholars make bad historians, but he never tired of brainstorming with me about ways to tap into history to strengthen human rights arguments.

Dad’s most devoted collaborator and partner was my mom. Dot was a passionate supporter of Florida history and preservation, working and traveling with Gene, often with family in tow. She developed archival expertise and took it to private archives around the world – Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Spain, among other far-flung locations – working alongside Dad to preserve and share fragile records. When dad’s work took him to St. Augustine, she took a job as a librarian for the St. Augustine Foundation, cataloguing the collection and helping countless library visitors explore local history and their genealogies.

It’s been really wonderful hearing from the women Dad mentored, during an era when women historians faced structural barriers and hostility in the male-dominated discipline. As one of his mentees shared, “I loved my dissertation director too but Gene was really the mentor who shaped my whole career.” Another said, “your father was instrumental in my living so happily in Sevilla since 1976. He was my mentor for many years: everything he taught me in the archives, how he approached life, his calm but determined voice, his enormous generosity, his ability to communicate such intelligence so easily.” A co-author captured how we are all feeling: “So many of us are intellectually and personally adrift without him.”

TRIBUTES FROM FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES

TAFFI FISHER ABT, DAUGHTER OF MEL FISHER

It’s hard to believe Gene is gone from this earth. I have known his family for as long as I can remember. We moved here in 1963 when I was two years old. I remember as a child going to church and Sunday school with the Lyon family at a church Gene and Dottie and my parents helped found, Christ by the Sea United Methodist on A1A, Vero Beach. Gene attended services, taught Sunday school and helped this church throughout his lifetime.

As a child, I spent oodles of time hanging out at their home, their daughter Katie and I, were closest in age and played together often. Katie went on later to a successful career in social work, which Gene always confided to me that he didn’t think paid her enough.

His wife Dottie always baked homemade cookies for us, made us lemonade, and taught us to sew clothes by hand for our Barbie dolls. Gene was always in the background, reading something.

Katies big brother, Kenny, now a very prominent professional musician, was always playing his guitar in the background. Peggy, whom I’ve grown close with over the last decade, was a beautiful, tall like her father, blonde teenager, and seemed so glamorous to me. She became an accomplished, respected, and now retired attorney in Vero Beach.

Mary Beth was the baby, happy go lucky, and always tagging along with Katie and I. They had a VW van I loved to ride in. I missed them when we moved to Key West in 1970.

As a young adult, I had the honor of serving with Gene for many years on the board of directors for the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society, founded in 1982 by my folks. After the motherload of the Atocha was found, he and his wife sold some of the treasure they received as their share of the haul to build a pool at their home. He called it the Atocha Pool.

He had an innocent and mischievous sense of humor. Even after I relocated to the Vero area in 1989, sometimes Gene and I would share a small charter plane at the Sebastian airport to fly to Key West and attend meetings. It was always something watching him climb into those tiny little 4 or 6 seater planes, he was so tall he had to practically fold himself in half to get in.

He loved to talk about his beautiful wife, how they met, how they were taking up yoga, and he often talked about how very proud he was of the accomplishments of all of his children. He told me he had joined a new social group at his church, the OWLS, which stood for Older Wiser Livelier Seniors.

These past few years, I visited him for lunch several times and he boasted about his grandsons and their achievements, particularly in the Boy Scouts. He suggested I should write a ‘real’ biography of my parents, and he read some of my initial attempts, and constantly encouraged me to keep working on it. He also continually suggested some new shipwreck or other that he thought I should go after.

He was persistent and genuinely loved history and the stories behind the shipwrecks. Gene was one of the most intelligent, thoughtful, kind, diplomatic and soft spoken people I have ever known. I will always have nothing but respect and admiration for him and his family. I will miss him sorely as a friend.

CARL “FIZZ” FISMER, WORLD FAMOUS TREASURE HUNTER, 1715 FLEET AND 1733 FLEET

I first met Gene in 1981 or 82. He had permission to work the Rio Mar site and ask D.L. Chaney and I to work it for him.

Now and then Gene would paddle out in a rubber boat to pay us a visit. I don’t remember the Silver count, but we got 12 gold coins that year.

I met Jack Haskins when D.L. ask me to work on the RV Wasp in 1980. At first Jack didn’t like me. His motto was Don’t Educate ‘Em, You’re Only Training the Competition.”

When D.L. passed away the following year, Jack was stuck with me, for 32 years. Jack and Gene had a research agreement that they would help each other when needed. They often collaborated. They kept in pretty close touch.

After Jack passed away, at the next Treasure Hunters cookout one of the guests told me Gene wanted to see me, and he was in one of the hotel rooms. It was hot out. I went in and Gene shook my hand extra long and said, “Carl, I want to Thank You for taking care of Jack the way you did.” I wasn’t expecting that, and can tell you now, that it was hard not crying.

I did later though. We talked about Jack and I assured him that Jack owed me nothing. I told him that my last visit to see Jack that he was coherent, and worried about me, saying, “I don’t know how I’m going to pay you back.” My answer was, “Hey Dumb butt, I’m paying you back for a 32-year education.”

Gene smiled. Those two meant more to each other than was public knowledge. Jack often made reference to

Gene’s research, as well as Gene. What luck for the people that hired them because if a problem arose you had two of very best working on it.

Probably right this minute the two of them are still digging into thousands of pages on the 1622 Fleet.”

CURTIS WILLIAM ERLING WHITE, ATOCHA CREW MEMBER

I met Gene in 1980 at Treasure Salvors, Inc.’s headquarters and enjoyed a friendship that lasted until his passing. One of my most prized possessions in the scores of artifacts in my collection, the 1622 certificate signed by His Excellency Diego Colon, Jim Sinclair and Dr. Lyon.

BILL BLACK, SEARCH AND SALVAGE, SEBASTIAN, FLORIDA

Dr Eugene Lyon was one of the most unassuming men I have known, yet was an extremely influential historical scholar who contributed so much to the field of shipwreck salvage archaeology. Without Dr Lyon’s dogged research and keen mind, the wreck and main cultural deposit of the Atocha would probably never have been found and much of what is known of the 1715 and 1733 Fleets would still be a mystery as well.

The Treasure Coast, the Florida Keys and the global shipwreck salvage community all owe him a great deal of gratitude.

Fair winds and following seas, Gene. We will likely never see your equal again. Godspeed.

HONORS AND AWARDS

Dr. Lyon received the grade of Orden de Isabel la Catolica (Official Order of the Isabella) from King Juan Carlos of Spain and the grade of Comendador in the Order of Christopher Columbus from the President of the Dominican Republic.

He returned to the University of Florida as an Adjunct Professor of History and served on the Board of Directors of the Florida Endowment for the Humanities and the Florida Historical Society. In 2003, the Florida Historical Society presented him the Jillian Prescott Award for lifetime service to Florida history.

In April 2019, Dr. Lyon was honored as Chairman Emeritus at the Santa Elena Foundation in Beaufort, South Carolina. His work and a bronze Columbus statue are on display at the center, commissioned by the National Geographic.

ABOUT THE WRITER

Allen Balogh is the author of Black Sails 1715 and co-author of the award-winning Goat with the Glass Eye. He penned the popular article, “When the pirates scoured the Treasure Coast, IRM Summer Edition 2019. Cuba and the 1715 Fleet, A Perilous Voyage will be published in the fall of 2020. A children’s pirate book, Mimi’s Mermaids, will be out in the summer of 2020. Contact: BlackSails1715@gmail.com.